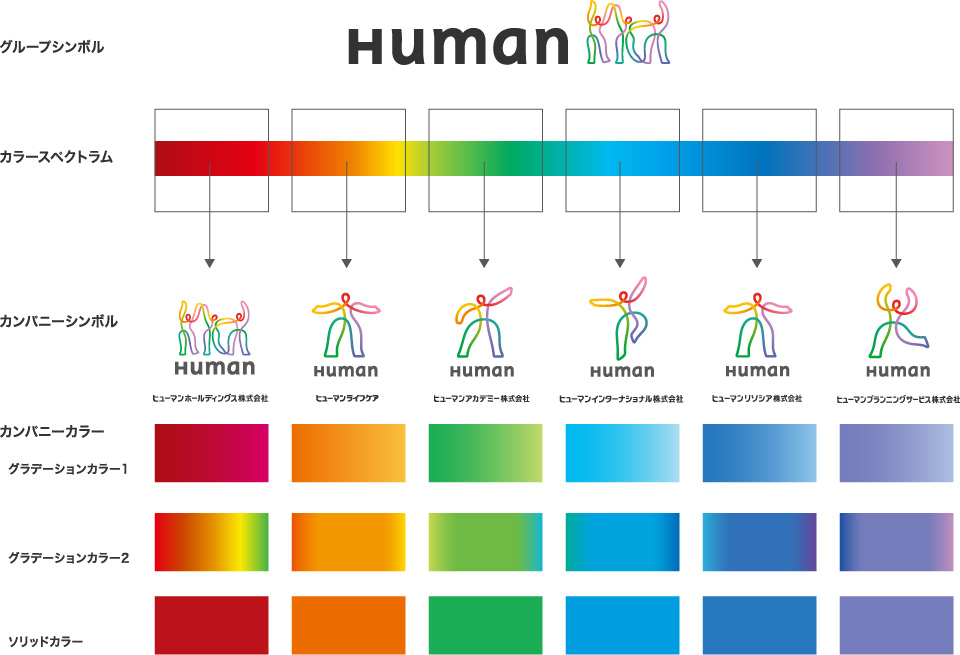

- Human Holdings new logo

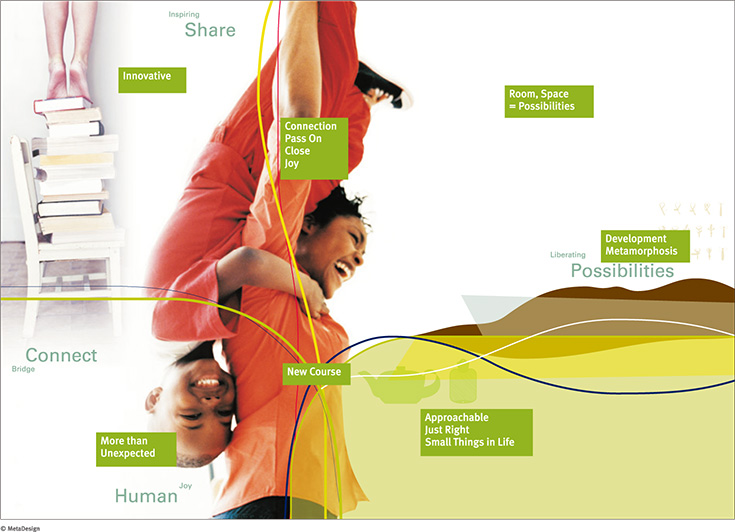

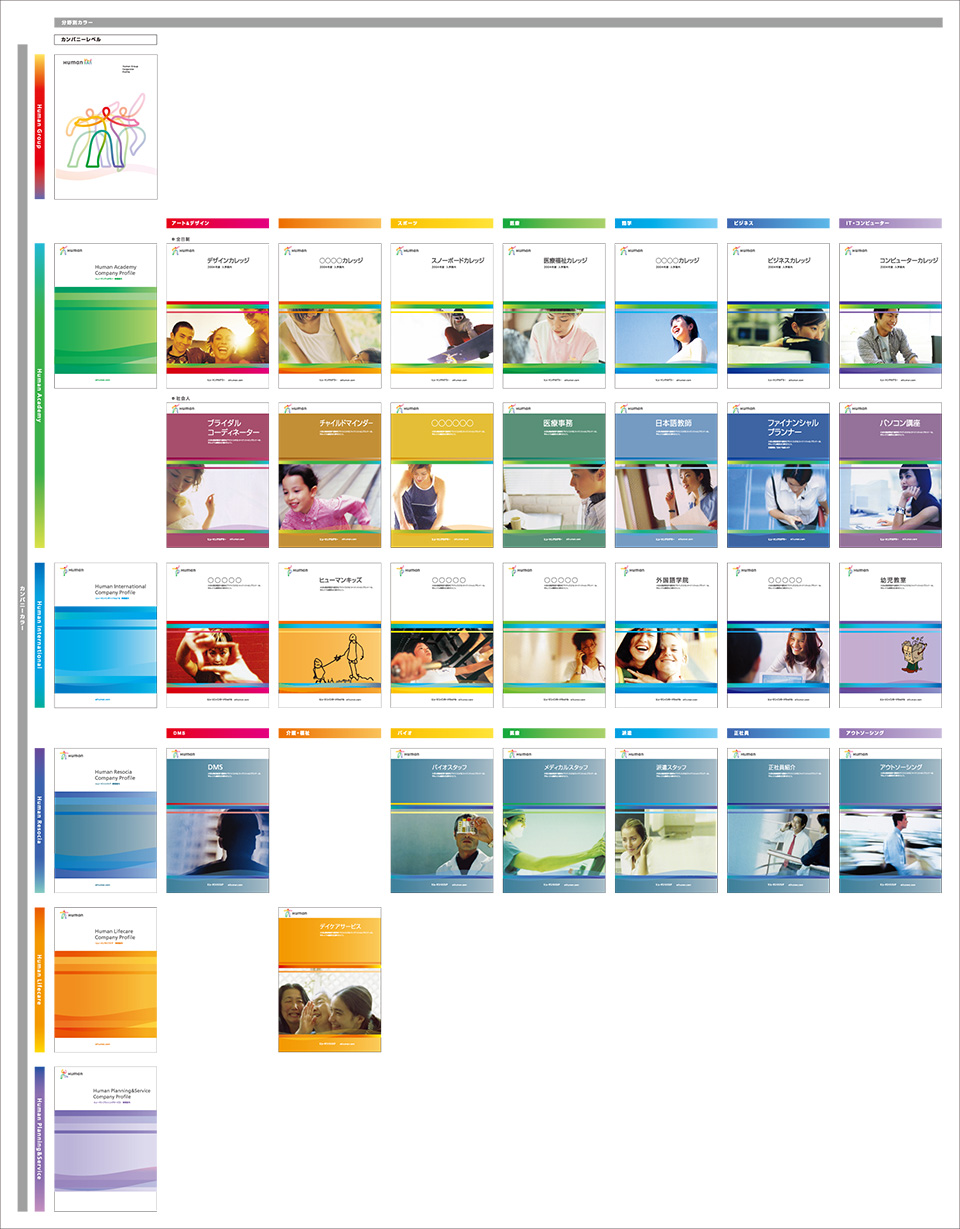

- The project was a joint operation by Meta Design of Berlin and AXHUM Consulting of Tokyo. The Human Holdings mark symbolizes the three policies of ‘educational renaissance, academia-industry cooperation, and international education’.

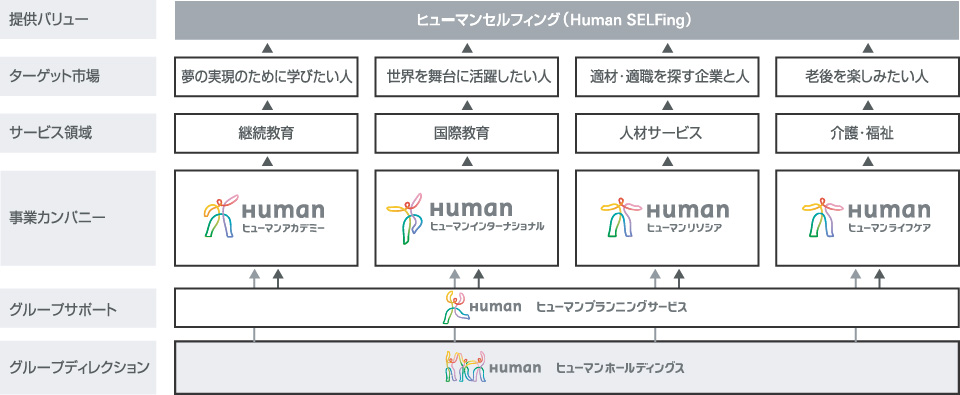

Goals and tasks of The branding project

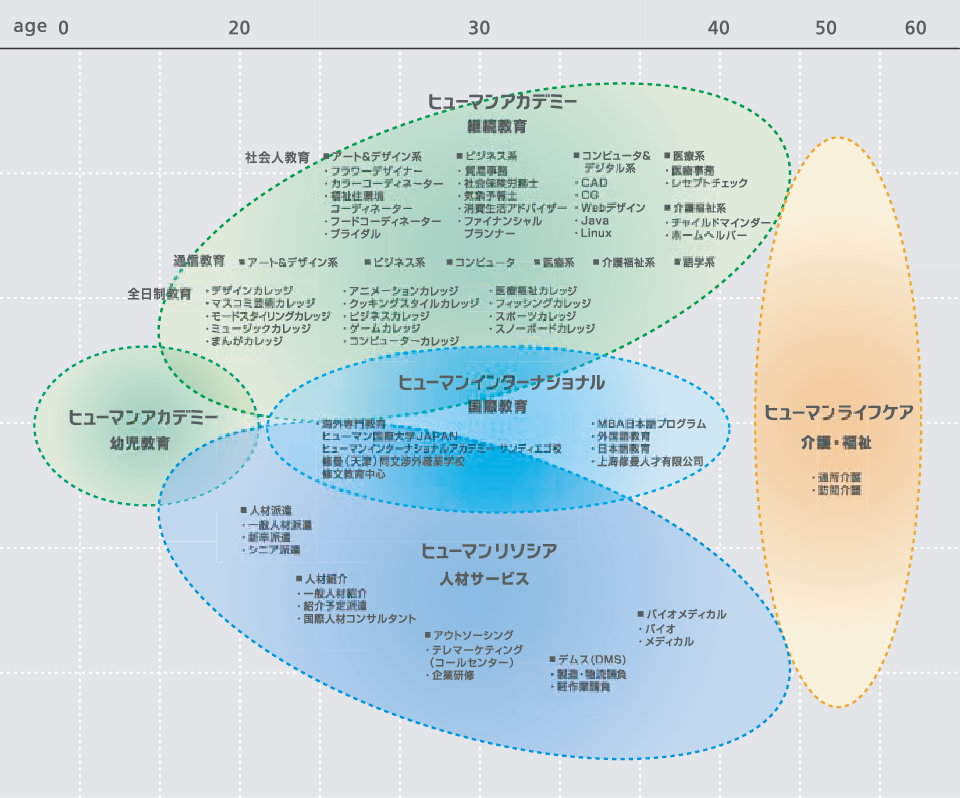

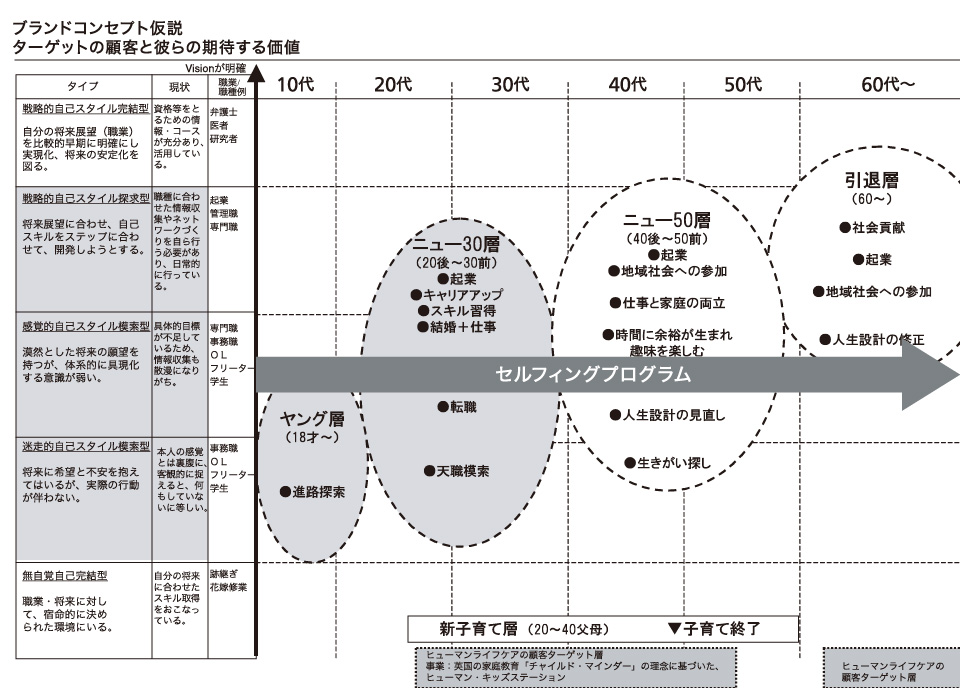

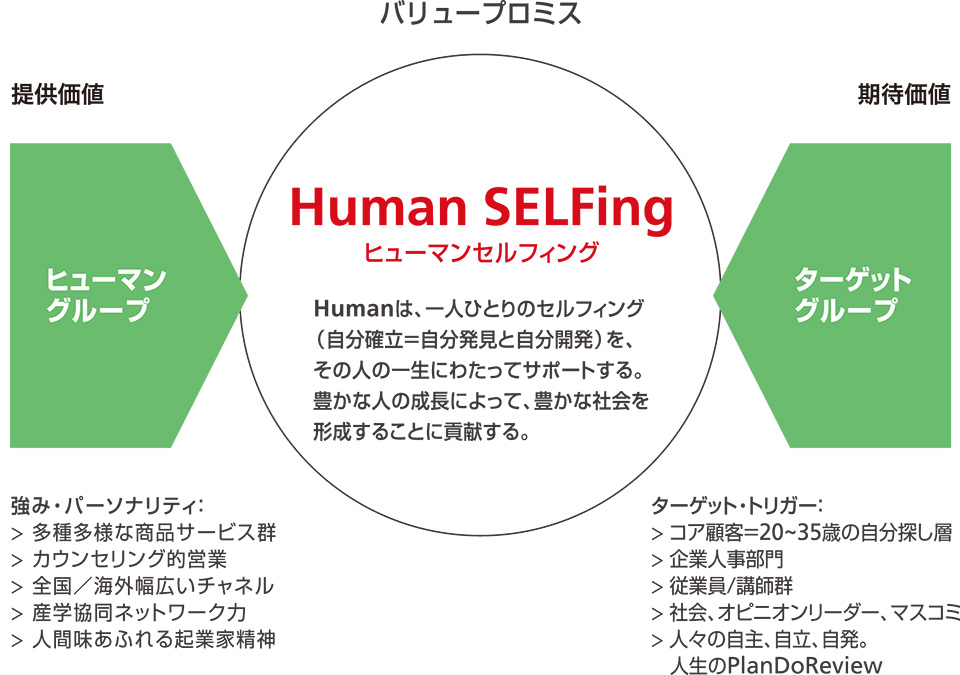

The Human Group is a collection of companies active in business sectors related to human resources and includes in its ranks Human Academy, engaged in adult education, and Human Resocia, engaged in staff supply and recruitment agency services.

Specifically, Human Academy, which runs several hundred educational programmes, is Japan’s largest school for the acquisition of qualifications and professional education, and its synergistic effect with Human Resocia, which supplies human resources to society, is a distinguishing feature of the Group and a point of appeal.

The Human Group experienced dramatic business expansion as its operations seemingly multiplied, however there were signs of its identity becoming blurred as its business direction tended to become diffuse.

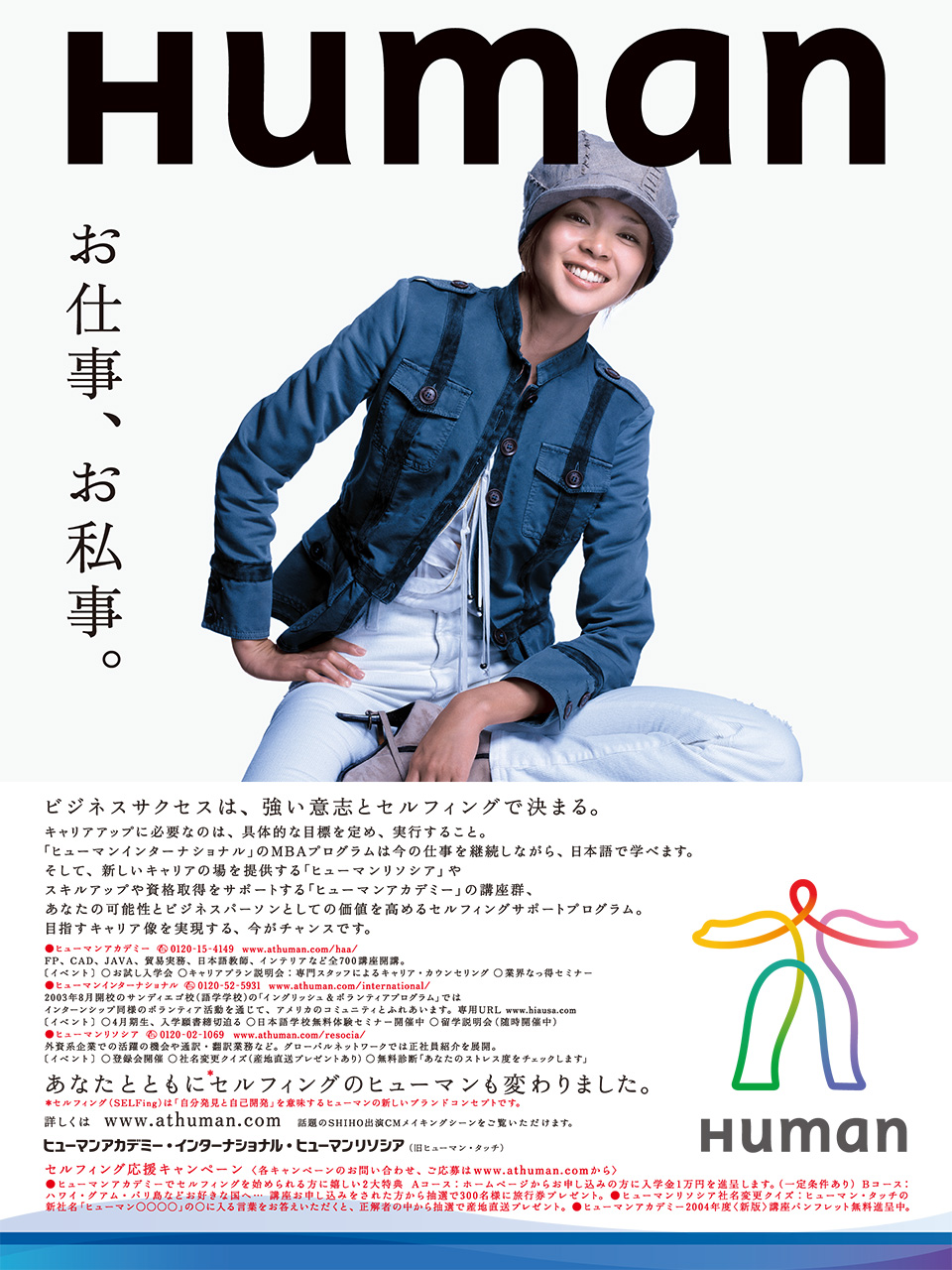

The prime task of the branding project was therefore to implant in the corporate group with its strong centrifugal force, something to act as its core value while providing its organisation with a centripetal force, coherence and direction. A simultaneous task for the medium-term business management strategy was to respond to the need for a branding strategy which would effect the switch from ‘flow-type’ marketing centred on aggressive promotional activities, to ‘stock-type’ marketing in which people would be attracted by the appeal of the Human brand.

Changes in the Japanese human resources market

Major factors in the Human Group’s expansion involved structural environmental changes in the Japanese market. The first major factor was the collapse of the ‘Japanese-style business management’ of the corporations which had supported Japan’s high economic growth. The drastic restructuring provoked by the prolonged recession which began in 1990, turned corporations into lean high-performing machines but at the same time there was a glut of human resources which had become unemployed. Meanwhile, the introduction of American-style performance-based staff management, which was seen as the global standard, led to a great mobility of human resources.

In the last ten years, the ‘lifelong employment’, ‘age-based seniority’, ‘in-house training’, and ‘family atmosphere’, which had been the hallmarks of Japanese-style business management disappeared all at once. The second factor was the mismatch between education and society, and the rapid increase of part-time workers. There were more than three million young people in Japan who had not found permanent jobs by their mid-20s and who had therefore missed out on a stage in life important for individual career development.

Against this background of environmental change, there was a large increase in the number of people seeking self-discovery in the face of uncertain future prospects, and a large number of magazines appeared dealing with job-seeking and acquisition of qualifications.